|

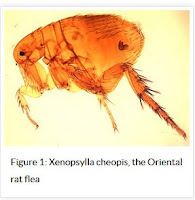

| Credit CDC |

#12,933

Murine typhus, aka flea-borne typhus, is a bacterial disease caused Rickettsia typhi - and while not terribly common in most of the United States - it is most often reported in California, Texas and Hawaii. Although some cases will recover without treatment, others can become sick enough to require hospitalization, and deaths are not unheard of.

Not to be confused with Typhoid Fever - which is caused by a Salmonella Typhi infection that can (rarely) be transmitted from one person to another - Typhus is acquired from contact with infected fleas that live on rodents, possums, raccoons and cats.While I've mentioned the occasional outbreak (see Disease Transmission At The Human-Animal Interface), Typhus - for many decades - had been pretty rare in the United States. But like so many other emerging and reemerging zoonotic diseases, we are increasingly seeing it crop up in new, or unusual locations.

Texas reports anywhere from a couple of dozen to a couple of hundred typhus cases each year, but until recently most cases have been reported in the south and central part of the state, along the coastline.

Over the past few years, that geographic distribution has begun to change.After going 8 decades without a case - in 2012 Galveston, Texas reported two cases prompting an epidemiological investigation that led to the identification of 12 more cases in 2013 (see MMWR Reemergence of Murine Typhus in Galveston, Texas, USA, 2013).

The authors wrote:

Dynamic shifts in the epidemiology and transmission of murine typhus are not unprecedented. Although the rat-to-rat cycle of transmission by fleas is often referred to as an urban cycle, the rural South experienced high rates of murine typhus in the 1940s as a result of a proliferation of rats after a change in crop production from cotton to peanuts, because rats were attracted to the peanuts as a source of food (13).

In southern California, opossums infested with R. typhi– and R. felis–infected cat fleas (C. felis) have been associated with a shift of fleaborne rickettsioses from the urban center of Los Angles to suburban areas (14). This suburban cycle of transmission involving C. felis plays a recognized role in Corpus Christi, Texas, a coastal city ≈220 miles southwest of Galveston (1). Additionally, this cycle has been suspected in a recent outbreak of murine typhus in the central Texas city of Austin (15).This year, the number of Typhus cases in Texas is expected to well exceed last year's (21st century) record of 364 cases, and the DSHS notes increased activity in the urban areas of both Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston.

Since the signs of symptoms of Typhus are similar to many other diseases, the DSHS has today issued the following alert to health care providers to increase their clinical suspicion, and to urge prompt treatment with antibiotics (even before lab results are returned).

HEALTH ALERT

Increased Flea-borne (Murine) Typhus Activity in Texas

November 30, 2017

Due to increased reports of flea-borne (murine) typhus during 2017 from multiple areas of Texas, DSHS is requesting that healthcare providers increase their clinical suspicion for patients presenting with fever and one or more of the following: headache, myalgia, anorexia, rash, nausea/vomiting, thrombocytopenia, or any hepatic transaminase elevation. The diagnosis of flea-borne typhus relies on a high index of clinical suspicion and on results of specific laboratory tests.

Flea-borne typhus is caused by infection with the bacterium Rickettsia typhi (or R. felis). Rat and cat fleas are the primary vectors. Transmission to humans can occur when infected flea feces are scratched into a bite site or another abrasion in the skin, or rubbed into the conjunctiva. Rats, opossums, and cats are thought to be the primary reservoirs for the disease in Texas.

People with typhus report non-specific symptoms including fever, headache, chills, malaise, anorexia, myalgia, rash, nausea, and vomiting. Laboratory findings may include thrombocytopenia, hyponatremia, elevated hepatic transaminases, and CSF abnormalities consistent with aseptic meningitis. Although flea-borne typhus is often a mild, self-limited illness, more than 60% of reported cases are hospitalized. Since 2003, eight deaths have been attributed to flea-borne typhus infection in Texas. When left untreated, severe illness can cause damage to one or more organs, including the liver, kidneys, heart, lungs, and brain. As with other rickettsial infections, prompt antibiotic treatment is recommended; treatment should not be delayed pending diagnostic tests. Additional clinician guidance on typhus can be accessed at the CDC website: https://www.cdc.gov/typhus/murine/index.html

Over 2,800 cases of flea-borne typhus were reported in Texas between 2000 and 2016 [median = 157 cases/year; max = 364 cases/year (2016); min = 22 cases/year (2001)], and over 400 reported cases are expected for 2017. In previous years, typhus was primarily reported from South Texas, along the Gulf Coast (Nueces County), and Central Texas (Travis and Bexar counties). In 2017, increased typhus activity has been noted in the Dallas-Fort Worth and Houston areas. Cases are reported year-round, but the majority of typhus cases occur between May and July, with another peak in December and January. Typhus can occur in any age group, but over 25% of cases are reported among those between 6-15 years of age.

Laboratory Diagnosis of Flea-borne Typhus Infection

Laboratory testing is required to confirm a diagnosis of flea-borne typhus. The most efficient and readily available diagnostic method to confirm infection with R. typhi is detection of IgG antibodies to R. typhi using an indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) test in acute and convalescent serum specimens collected at least 3 weeks apart. However, because antibodies for rickettsial diseases can be cross-reactive, specimens should be tested against a panel of Rickettsia antigens, including, at a minimum, R. rickettsii and R. typhi, to differentiate between spotted fever group and non-spotted fever group Rickettsia spp. Many commercial laboratories offer rickettsial serology testing, but it should be noted that ELISA or EIA tests are not reliable for rickettsial disease diagnosis. Molecular testing is a more definitive testing option. Whole blood collected within a few days of illness onset may be tested by PCR in an attempt to detect Rickettsia spp.

Rickettsial panel IFA testing is available at the DSHS Laboratory. It is desirable to submit a volume of 2 mLs of serum per specimen. Serum samples may be refrigerated for transport if the specimens will be tested within 48 hours. If not, ship frozen at 2°-8°C. If molecular testing is preferred, whole blood samples may be routed through the DSHS Laboratory to CDC. Guidance for the submission of specimens to the DSHS Laboratory for typhus testing can be found at: http://www.dshs.texas.gov/lab/mrs_mic_test_t2.htm#Typhus. Please contact the DSHS Laboratory at (512) 776-7514 during regular business hours with any questions pertaining to typhus diagnostic testing.

Disease Reporting

Flea-borne typhus cases are required to be reported to the local health department (LHD) within one week. If there is no LHD, reports can be made to the Regional DSHS Zoonosis Control Office. Contact information for Regional Zoonosis Control staff is available at: http://www.dshs.texas.gov/idcu/health/zoonosis/contact/.

Last updated November 30, 2017You can find more information on the CDC's Typhus Home page.