#18,048

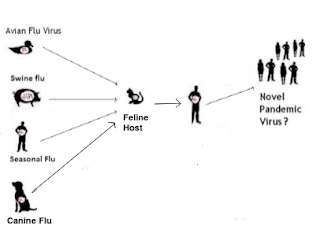

It is frustrating that six weeks since we first learned that HPAI H5 had been detected in American dairy cows and 5 weeks since the first human infection was reported, the size and scope of this spillover event remains murky.

- Just 1 case has been identified, but there are credible anecdotal reports of `many' symptomatic farm workers who have refused to be tested.

- We've seen reports - both in the media and in statements made by APHIS/USDA officials - that they've met `resistance' from farmers who don't want their herds tested.

- And recent media reports (see here, and here) suggest that some state agencies are not cooperating with the CDC or USDA (Note: The CDC has no authority at the state level unless they are invited in, and apparently some states have elected not to do so).

As a result, despite strong evidence suggesting the HPAI H5N1 virus is widespread in dairy cattle, only 36 herds across 9 states have been identified. And only one herd has been added to the list over the past 18 days.

There may also be community cases of human H5N1 infection which have gone undetected. But without testing, we simply can't know.

Turf wars between local and federal officials are nothing new, although until fairly recently the CDC appeared immune. The deep political divide over the agency's COVID response appears to have changed that dynamic.

I try not to ascribe motivations and intent to people I don't know, who are working under constraints I can only imagine. But this is a very dangerous game, and if H5N1 gains transmissibility in humans, everyone loses.

Three weeks ago the CDC came out with strong recommendations for protective gear to be worn by people working with potentially infected animals. It is unclear however - whether, or how much - they are being used.

Given the difficulties in trying to do farm work in protective gear, the costs (in lost time and materials), and the public's general distaste for wearing face masks after COVID, I suspect adherence is low.

As noted above, properly donning and doffing PPEs requires both training, and separate `designated clean areas'. But when cattle are visibly sick, or when they have tested positive for HPAI, wearing PPEs becomes crucial.

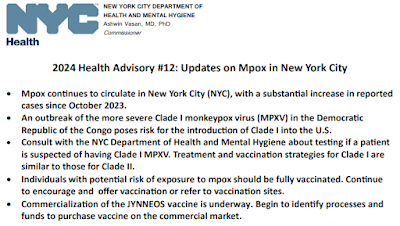

Yesterday the CDC held a conference call (see readout below) with `state health officials, public health emergency preparedness directors, state epidemiologists, and state public health veterinarians, and leadership from public health partner organizations' discuss farm worker protection using PPEs.

Quite telling is the following sentence in the last paragraph (emphasis mine).

First the CDC's statement, after which I'll have brief postscript.CDC offers real-time support for state and local public health officials, as well as staff who are ready to deploy within 24 hours, if requested.

Readout of CDC Call with State Public Health Partners Regarding Avian Influenza and Farmworker Protection

Media Alert

For Immediate Release: Monday, May 6, 2024

Contact: Media Relations

(404) 639-3286

media@cdc.gov

May 6, 2024 – Today, CDC Principal Deputy Director Nirav D. Shah met with state health officials, public health emergency preparedness directors, state epidemiologists, and state public health veterinarians, and leadership from public health partner organizations to discuss farmworker protection and personal protective equipment (PPE) for avian influenza.

CDC asked that jurisdictions make PPE available to workers on dairy farms, poultry farms, and in slaughterhouses. Specifically, CDC asked state health departments to work with their state agriculture department counterparts and partners in communities, such as farmworker organizations, that can help coordinate and facilitate PPE distributions.

Shah recommended that states prioritize distribution of PPE to farms with herds in which a cow was confirmed to be infected with avian flu, noting that some states have already distributed PPE to dairy farms. Jurisdictions were asked to use existing PPE stockpiles for this effort. Shah also briefed state officials on how to request additional PPE from HHS/ASPR’s strategic national stockpile, if needed.I suspect that a lot of people are banking on the idea that H5N1 will eventually burn itself out in cattle, and that since it hasn't sparked a pandemic after 20 years, it never will. While I hope both assumptions are correct, the downsides to getting this wrong are enormous.

Although CDC’s assessment of the immediate risk to the U.S. public from avian influenza remains low, Shah highlighted the importance of states acting now to protect people with work exposures, who may be at higher risk of infection. CDC has actively engaged with state and local health departments, farmworker organizations and public health veterinarians since first learning about the outbreak of HPAI in dairy cattle herds. CDC is also sharing information with staff at Federally Qualified Health Centers, who may care for farmworkers to help ensure that these staff are aware of the importance of PPE and the options to obtain it.

Shah reiterated the agency’s commitment to support state health officials, who are conducting the on-the-ground public health response to this outbreak. CDC offers real-time support for state and local public health officials, as well as staff who are ready to deploy within 24 hours, if requested. CDC will continue to provide states with the latest situational information and advice to help support their public health response efforts.

It is possible, of course, that even if we manage to contain it here, HPAI could spillover to humans in some other country next week or next month.But a robust, and transparent, investigation might yield valuable data to help us deal with that contingency. Meanwhile, the virus is indifferent to our political divides, economic concerns, or logistical constraints.

HPAI has time on its side, and will do whatever it is going to do, regardless of our plans or assumptions.Our only realistic option is to face the problem directly, prepare for whatever comes, and hope it is enough.